Article and photos by Katie Doke Sawatzky

Published Oct 1, 2018 3:30 PM

*This article was updated on July 30, 2020.

If you were raised in southern Saskatchewan, the word “prairie” comes naturally and you use it often to describe where you come from. For me growing up the word evoked images of yellow fields, canola dancing in the wind; the kind of landscape where your gaze is drawn upward, not towards mountains, but to the open sky. Saskatchewan is a Prairie province. I am from the prairies. I live on the prairies. Over the course of the past year, I have learned this ritual of description, so often repeated with pride, is a deception and delusion—crops, however beautiful, are not "prairie." The time has come for prairie people to acknowledge that the landscape by which they describe themselves is almost gone and that the value of what remains is threatened.

Endangered and not monitored

Temperate grasslands, which cover eight per cent of the Earth, are the most endangered ecosystem on the planet, with less than five per cent protected globally (Federal, Provincial, and Territorial Governments of Canada, 2010; Jenkins, 2009). In Saskatchewan, the figure, quoted by both the government and the conservation community, of how much native grassland is left is approximately 20 per cent. That estimate comes from a report by the Native Plant Society of Saskatchewan and is based on analysis of satellite imagery taken 24 years ago, which says the amount left is most likely a range of between 17 and 21 per cent (Hammermeister, Gauthier, & McGovern, 2001). Saskatchewan’s Ministry of Environment does not know how much native prairie is left and finding out is no easy task. There is no active provincial reporting or monitoring of the landscape by the province. In 2015, the ministry began the Prairie Landscape Inventory, which aims to find out how much native prairie is left. The ministry is currently testing modelling techniques in different areas of the province that will be able to differentiate native grass from tame grass in satellite imagery, something that is not done in other data products like the land-cover maps created by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. However, Ben Sawa, a habitat ecologist with the ministry, estimates the process will take anywhere from five to 10 years. In the meantime, more parcels of grassland are lost each year.

An eroding landscape

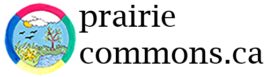

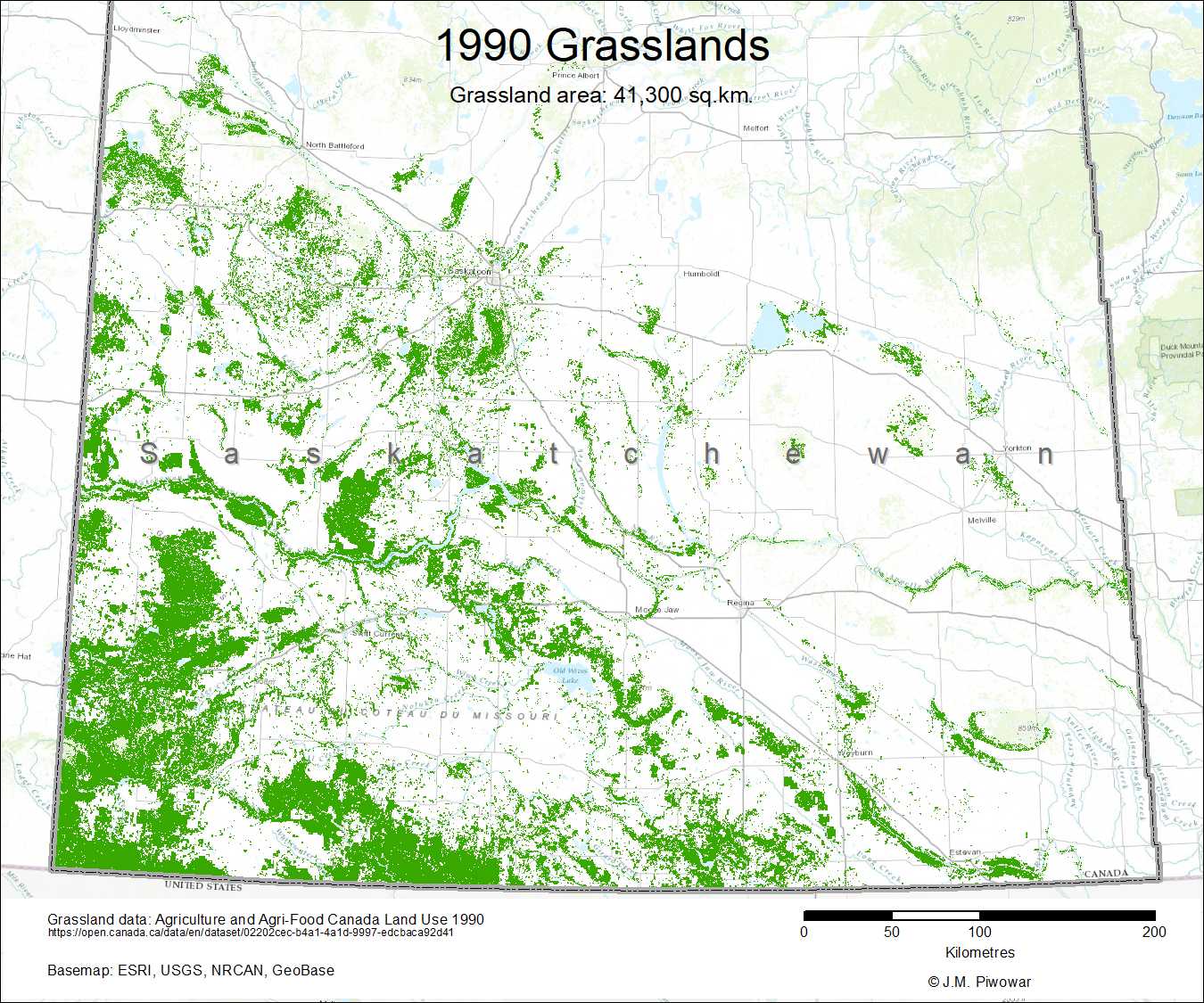

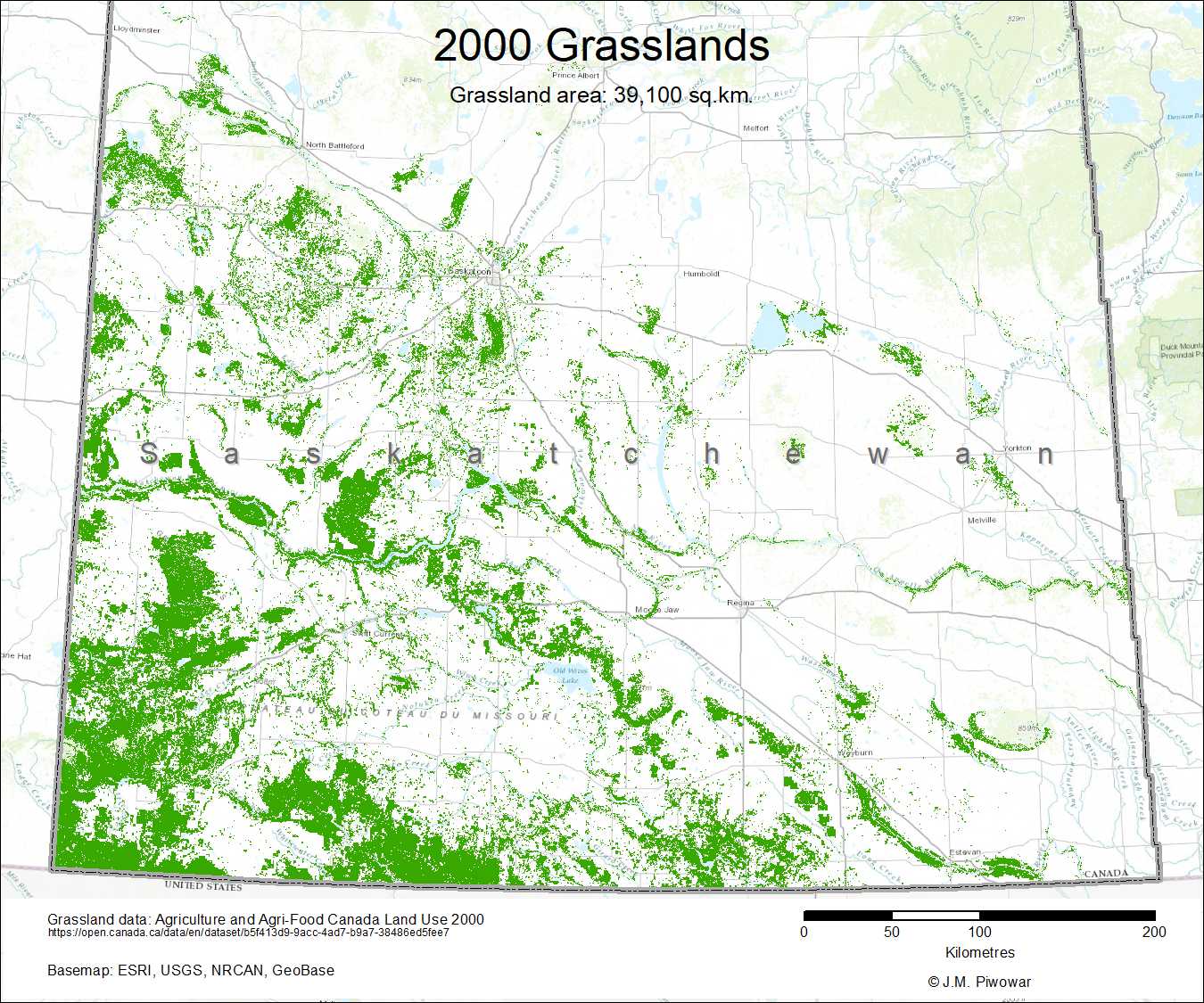

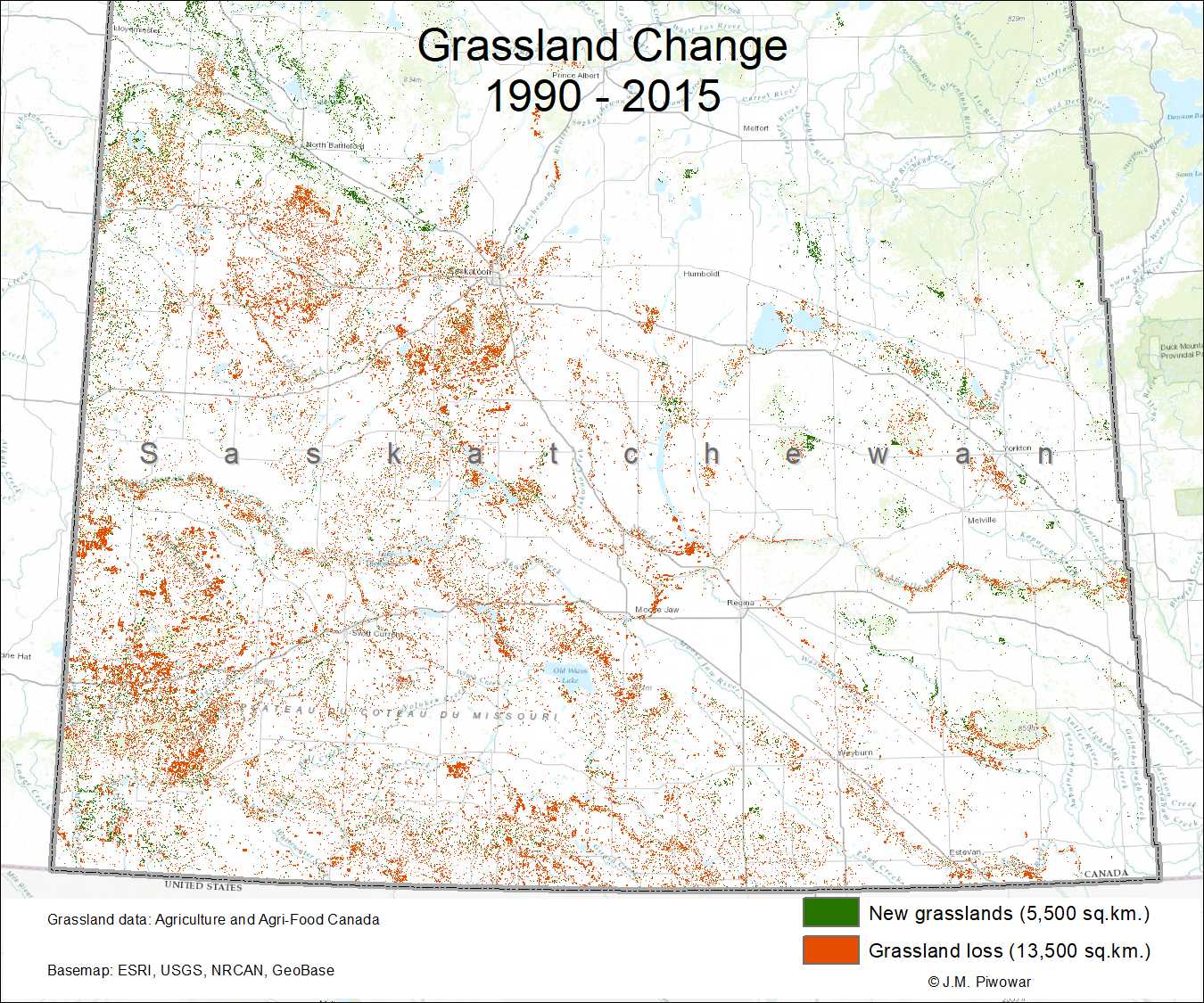

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada land-use and cropland-inventory maps, while not able to distinguish native from tame grassland without error, show a steady decline of grassland from 1990 through to 2015. Defining grassland as “Predominantly native grasses and other herbaceous vegetation, may include some shrubland cover,” an analysis of the maps by University of Regina geography professor Joe Piwowar, shows a decline of 3.3 million acres over twenty-five years* (Doke Sawatzky & Piwowar, 2019). As of 2015, 8.2 million acres of grassland remained in the province, which means that, out of the historical 60 million acres the Prairie ecozone once encompassed in Saskatchewan, only 13.7 per cent remains. This is 6.3 per cent less than what is currently quoted by the Ministry of Environment and Nature Conservancy of Canada – Saskatchewan Region.

*After this website was published, the author co-authored a paper with Piwowar, highlighting this research, which was published in 2019 in the journal Prairie Perspectives: Geographical Essays.

The Native Plant Society of Saskatchewan defines grasslands or native prairie as “open grassland interspersed with lakes, ponds, creeks, river valleys, shrubs and trees.” Before southern Saskatchewan was settled in the late nineteenth century, it was a landscape that supported Indigenous peoples, bison, and a “myriad of birds and insects” (Hammermeister, Gauthier, & McGovern, 2001).

In Saskatchewan, grasslands are geographically located in the bottom third of the province, in the Prairie ecozone. There are four ecoregions within that zone: the Cypress Upland, Mixed Grassland, Moist Mixed Grassland and Aspen Parkland.

Grasslands are one of the most biodiverse ecosystems on the planet, with fifty to 100 different species of grasses and wildflowers able to live within one quarter section of land (Mosher, 2012). In Saskatchewan, grasslands are home to more than 30 species at risk. Grassland birds species in the Great Plains have declined anywhere from 65 to 94 per cent since they were first counted in the 1960s (World Wildlife Fund 2017 Plowprint Report, 2017).

Besides providing habitat for diverse plants and wildlife, grasslands and the wetlands among them filter toxins from air and water (Wruck, 2003). The peat underneath and vegetation surrounding wetlands, along with the root systems of prairie grasses, stores vast amounts of carbon (Johnston, 2017). Canada Parks and Wilderness Society estimates that 2 to 3 billion tonnes of carbon per hectare lies within the first metre of uncultivated grassland soil in western Canada, which is the equivalent to removing approximately 150 cars from the surface of the Earth for one year (Vaadeland, 2016).

Despite these ecological benefits, the history of native prairie in Saskatchewan is nothing short of a tragedy. For more about prairie's environmental history, visit the Prairie and Peoples interactive timeline.

(For more about the Native Plant Society of Saskatchewan, go to https://www.npss.sk.ca/.)

A 2014 study done on fragmentation in the Canadian Prairie ecozone, calculates a range of remaining prairie land-cover types and, if sticking strictly to grassland (not including cover types like fallow and hay/pasture), concludes that there are 9.1 million acres left in Saskatchewan, which brings the figure remaining down to 15 per cent, more evidence of grassland's steady decline (Roch & Jaeger, 2014).

While grassland conversion to cropland isn’t what it used to be during settlement, it is still happening, something AAFC data also confirms. A simple search on the AAFC Land Use interactive map indicates that an average of 2.4 million acres of grassland were converted to cropland from 1990 to 2000 and from 2000 to 2010 (the land use inventory is only taken every 10 years) in the Prairie provinces. Here, the definition of “grassland” in the land use data specification is: “Natural grass and shrubs used for cattle grazing” (Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, 2010). The World Wildlife Fund’s 2017 Plowprint Report, which uses the AAFC data maps in its measurement of grassland conversion to cropland, confirmed the trend by stating that the highest rates of grassland conversion in the Northern Great Plains were in Saskatchewan and Alberta. The highest rates of conversion in the Great Plains, which extends from Saskatchewan to Mexico, were also found in Saskatchewan, in the aspen parkland, the transitional zone between the grassland and boreal forest.

Sarah Vinge-Mazer discusses the state of native prairie in Saskatchewan, what conservationists know about how much is left and how conservation efforts can improve to protect it.

Alberta miles ahead on monitoring ecosystems

Knowing a more accurate amount of native prairie left in Saskatchewan may not seem important to a now primarily urban Saskatchewan public (a 2011 census described only 30 per cent of the population as rural). On the flip side, it may be imperative, given that fewer people are living close to native prairie than ever before, meaning fewer eyes watching for changes in the landscape. Having that frontline information and more broad-scale provincial biodiversity monitoring helps government make informed policy decisions and keep the public up-to-date on human impacts on ecosystems. Such monitoring isn’t a pipe dream. Saskatchewan’s western neighbour, Alberta, has been forging a path in world-class ecosystem monitoring since 2007. The Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute, an independent, arms-length, not-for-profit organization, funded by government, universities, and industries like energy and agriculture, releases an annual biodiversity monitoring report and a biannual report on the human footprint in each natural ecoregion of the province.

ABMI has a total of 1,656 site locations that are actively monitored across the province, with around 600 sites in the Prairie region. The sites are 20 kilometres apart and visited annually, where staff measure plant growth, monitor species, percentage of different land-covers like water or trees, and complete soil analysis. They take photographs of the site and send any data about unknown species to taxonomic experts at the Royal Alberta Museum.

Majid Iravani, an applied ecologist at ABMI, said that while using satellite data for land-cover mapping is the protocol around the world, you need on-the-ground assessment to validate geospatial data, especially if you’re trying to gauge how much native prairie is left on a smaller-scale, like in a township, or quarter-section.

“When you want to implement something, like, land-conversion protocol, for example, … you really need detailed data, you really need data that you can trust,” said Iravani.

Iravani also says the benefit of this kind of systematic monitoring is that is provides a baseline of biodiversity, from which patterns of change can be tracked overtime.

“A monitoring program at this scale is important because especially for an area like Canada, we don’t know much about our biodiversity,” he said. “As long as we don’t know what we have, we can’t really manage it or protect it. We need to… understand what we have and then we need to assess what would be the reaction of these resources in terms of climate change or any land development and so on.”

“A monitoring program at this scale is important because especially for an area like Canada, we don’t know much about our biodiversity. As long as we don’t know what we have, we can’t really manage it or protect it."

As it stands right now, according to ABMI’s data, the grasslands region, which takes up 14 per cent of Alberta, has a human footprint of 57 per cent, as of 2017, meaning only 43 per cent is untouched by human disturbance. Within that 57-per-cent footprint, agriculture has done the most damage by far at 50 per cent, with things like energy and transportation following at 2.5 per cent. The parkland region, which is the transitional area between the grasslands and boreal forest, has seen even more human disturbance, with agriculture taking up 68 per cent of the region and an overall human footprint of 78 per cent.

Iravani says discerning the exact amount of native prairie left within these regions is difficult because of the difficulty of differentiating tame, native pastures, and cropland. He says ABMI hasn’t found a way to map Alberta's exact amount yet, but that subtracting the human footprint from the original geographical area, gives them a pretty good idea. Doing the math, with 57 per cent of 24 million acres of grasslands under human footprint, only 10 million acres remain, or 43 per cent. In the parkland region, that number drops to 22 per cent.

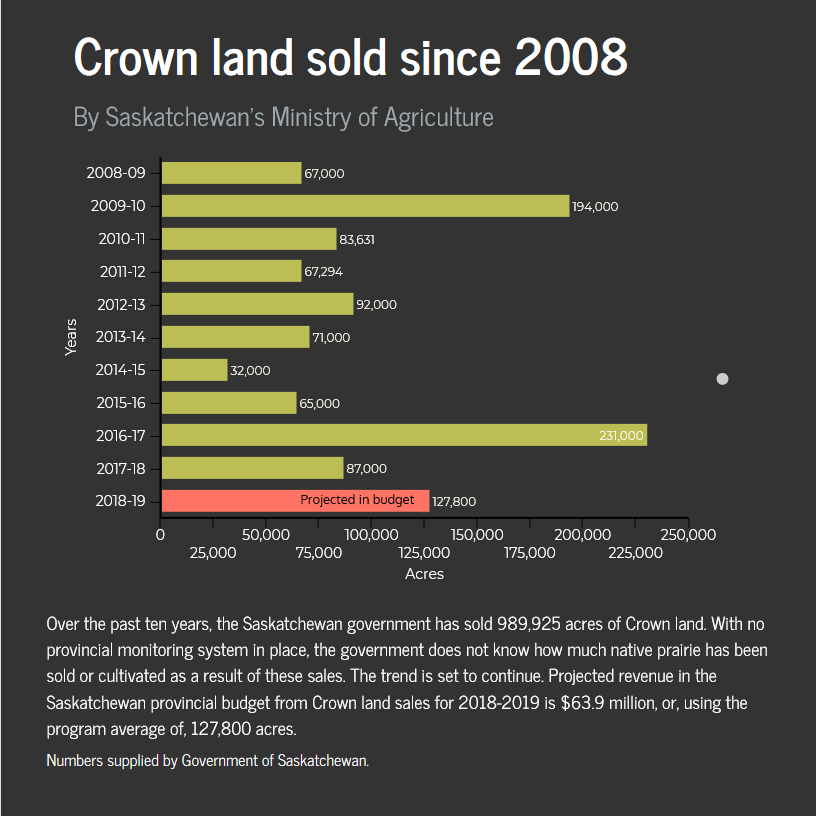

The threat of government disinterest

After record Crown land sales in the 2007-2008 budget year, the Saskatchewan government shifted to incorporate its selling of Crown land as a non-renewable revenue source in its 2008-2009 provincial budget, alongside natural gas, oil and potash. Since 2008, the Ministry of Agriculture has offered incentives for agricultural producers to purchase the Crown land they have been leasing from the provincial government. From 2008 to 2014, 500,000 acres of Crown land were sold under the Agricultural Crown Land Sale Program. Another incentive program began in 2015 offering leaseholders a 15 per cent discount, with the ministry estimating at the time that 600,000 acres would be sold under the program.

What is the connection with native prairie in Saskatchewan? With no provincial monitoring system in place, the government does not know how much native prairie has been sold or cultivated as a result of these sales.

Wally Hoehn, director of the lands branch for Saskatchewan’s Ministry of Agriculture, says that a random sampling of past sales doesn't indicate that a significant amount of Crown land sold by the ministry has been converted to agriculture. He’s confident producers are good stewards and doesn’t consider agriculture a big threat in today’s world.

“There is a bit of…the perception that as soon as a client gets this land they’re going to rip it up and tear it up. No, these guys are strong stewards,” said Hoehn. “They’ve done it because they know it’s the right thing to do and they continue to do the right thing ..., whether it’s under a Crown lease or whether it’s under private ownership.”

But Hoehn also says once Crown land is sold, the ministry no longer knows whether native prairie will remain and that he currently doesn’t know how much native prairie has been sold through Crown land sales.

“It would take a lot of time to sort those (numbers) out,” he said.

Despite Hoehn’s confidence, the grassland decline and conversion captured by AAFC data and the World Wildlife Fund in Saskatchewan show a different story. Combine this with the facts that the Ministry of Agriculture only audits or monitors its leased grassland at the time of lease renewal or when there’s a complaint and that no provincial monitoring of native prairie is undertaken by the Ministry of Environment, it’s not a surprise that grassland continues to degrade, slowly but surely.

Hoehn says the ministry currently relies on the public to do monitoring.

“Our best monitors are people out in the public, who know that it’s Crown land and know what can and can’t go on on it,” he said. “They will call us and say we don’t think this should be going on in there and we’ll go out there and do an inspection."

The Saskatchewan government has also shown a disinterest in supplying pasture management on its own Crown land.

In 2013, a year after the federal government announced it was cutting the Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration’s Community Pasture Program (PF pastures) from its budget and returning the pastures to the Prairie provinces, the Saskatchewan government decided to lease each of its 62 pastures separately, a land-base of 1.8 million acres (the majority of which is native grassland). Instead of continuing the PF program's third-party management, the province is leasing to patron groups who incorporated into businesses, ending the legacy of the community-pasture model, which provided world-class sustainable management of the grasslands. The PF transition ended on April 1, 2018.

In the spring of 2017, the Saskatchewan government cut the provincial Saskatchewan Pastures Program, which was even older than the PF system and responsible for 50 pastures, totalling 780,000 acres. According to provincial government, since 1922, when the SPP started, “the agriculture industry has become a strong driver of Saskatchewan’s economy, and the program is no longer necessary.” The SPP pastures are currently transitioning to a 15-year long-term lease arrangement with patrons, similar to the PF pastures.

Legislation offers little protection

Native prairie in Saskatchewan is protected by legislation like conservation easements, which place legal restrictions on the title of a piece of land that protect its natural ecosystems, restrictions such as no cultivation or new buildings. The Wildlife Habitat Protection Act protects designated Crown lands with ecological value from being sold. But in 2010, the Ministry of Agriculture amended the WHPA so that lands held under its legislation could be assessed and possibly sold, depending on their “ecological value.” In 2014, the ministry determined while land with “high ecological value” cannot be sold, lands with “moderate ecological value” can be sold with a Crown conservation easement (easements held by the Crown, not the landowner), and lands with “low ecological value” can be sold with no restrictions. Landowners can appeal to have Crown conservation amendments on their lands amended or terminated, and the minister, according to The Conservation Easements Act, can accept the application if he “is satisfied that it is in the public interest to do so.”

When asked why all Crown land sold in Saskatchewan’s prairie region isn’t protected with easements considering the endangered state of temperate grasslands, Hoehn said he doesn’t consider all parcels of high ecological value just because of that fact.

“I’ve been in arguments where they’ll argue that a road allowance is high ecological value. I mean it’s all got to be relative and in perspective is how I look at it,” said Hoehn. “I mean there’s a desire from our clients to quit leasing this land and get some equity in it…. We looked at our inventory and said, ‘Okay there is this group in the middle that is moderately important. We think we can sell ‘em and we’ll put a Crown conservation easement on it.’”

In 1997, Saskatchewan’s Ministry of Environment launched the Representative Areas Network (RAN). The goal of RAN is to conserve 12 per cent in each of the 11 ecoregions in the province.

“Each designated site helps to conserve Saskatchewan’s native biological diversity and will be used to benchmark or as a control area when assessing ecological health in areas outside of the representative area sites,” states Sawa.

Currently, the province conserves only 5.9 per cent of moist-mixed grassland and 5.6 per cent of aspen parkland, two ecoregions in the prairie ecozone. Not only does this fall short of RAN’s own goal but also of national and international conservation targets. Nineteen of the Aichi targets, set in 2010 by the United Nation’s Convention on Biological Diversity, were adopted by Canada in 2015. The eleventh target aims to protect at least 17 per cent of all terrestrial and inland waters. According to Jennifer McKillop, a former official with the Ministry of Environment and now the director of conservation for Nature Conservancy of Canada Saskatchewan, Saskatchewan hasn’t reached nine per cent.

Wally Hoehn with the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture comments on the sale of native prairie through Crown land sales and how the ministry monitors its leased rangeland.

Conservation organization profiles

Who is trying to protect native prairie in the province? Here are a few profiles of organizations in the province of Saskatchewan. While these organizations provide networking and some protection for native prairie they do not do wide-spread monitoring of the landscape. Because of their funding or their structure, some can’t speak up when prairie protection is put at risk through government divestment.

Saskatchewan Prairie Conservation Action Plan (SK PCAP)

Saskatchewan’s Prairie Conservation Action Plan is a non-profit organization that provides networking opportunities and information for its 29 partners, all of whom have a stake in conserving prairie but for different reasons. Members range from the Saskatchewan Stockgrowers’ Association, of which PCAP is a subcommittee, to the federal and provincial governments, universities, to smaller non-profits like the Native Plant Society of Saskatchewan. Members are required to attend at least one meeting (there are three) per year and some contribute funding. Core funding comes from the Ministries of Agriculture and Environment and some other conservation organizations. There are four staff, three of whom work by contract. PCAP conducts public outreach activities during Native Prairie Appreciation Week in June and classroom initiatives. Every four years it puts forward a framework agreed upon by all stakeholders that establishes goals and focus areas. The current framework has three broad goals, which include, raising awareness, promoting responsible land-use on native prairie as well as ecosystem management.

Carolyn Gaudet, the manager of PCAP at the time of writing, says bigger organizations don’t intimidate smaller ones and that any decisions are reached by consensus, but that PCAP isn’t an advocacy group. For example, she said PCAP as an entity couldn’t comment on the Ministry of Agriculture’s decision to divest from its provincial pastures in 2017 because the ministry is a PCAP partner.

For more information about PCAP, go to www.pcap-sk.org.

Nature Conservancy Canada Saskatchewan Region (NCC Saskatchewan)

Currently, NCC Saskatchewan is responsible for over 150,000 acres of land in the province, mostly in the prairie ecozone. The lands are either owned by NCC or under conservation easements, which place legal restrictions on the title of a piece of land that protect its natural ecosystems, restrictions such as no cultivation or new buildings. NCC currently holds 200 conservation easements, which are held in perpetuity. The organization develops property management plans to show landowners where species-at-risk live and shares information about current threats to those species, like oil and gas development or ATV use, for example. NCC builds stewardship actions into the management plan to address the threats and monitors the health of each property annually.

NCC’s monitoring data is only completed on lands they manage and isn’t available publicly, although it is submitted to the Saskatchewan Data Conservation Centre. NCC is funded by the federal and provincial governments, private donors, foundations and corporate sponsors. It is a registered charity and NGO.

For more information about Nature Conservancy Canada Saskatchewan Region, go to http://www.natureconservancy.ca/en/where-we-work/saskatchewan/.

Saskatchewan Conservation Data Centre (SKCDC)

The SKCDC was founded in 1992 by the Ministry of Environment and The Nature Conservancy (U.S.A. and Canada) and is now a partnership between the province and Nature Saskatchewan. Located in the Ministry of Environment’s Fish, Wildlife and Lands Branch, the five staff members gather and maintain data on species in Saskatchewan. SKCDC is a member of NatureServe and NatureServe Canada, which are national and international conservation organizations compiling data on species and ecosystems. SKCDC’s website says it currently holds records for 3,100 species. It provides regularly updated lists of species at risk in the province and resources for reporting invasive species. It also provides links to the Saskatchewan Breeding Bird Atlas and HABISask, an online mapping application for hunting and fishing.

Sarah Vinge-Mazer, who is a botanist with SKCDC, says while the organization focuses on species conservation, at this point in time they don’t have a community ecologist on staff to help gauge the status of native prairie as a whole.

For more information about Saskatchewan Conservation Data Centre, go to www.biodiversity.sk.ca.

Work cited

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. (2015). Annual space-based crop inventory for Canada. Centre for Agroclimate, Geomatics and Earth Observation. Retrieved from http://www.agr.gc.ca/atlas/supportdocument_documentdesupport/annualCropInventory/en/ISO%2019131_AAFC_Annual_Crop_Inventory_Data_Product_Specifications.pdf

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. (n.d.). ISO 19131 - Land use 1990, 2000, 2010, Data product specifications. Retrieved from http://www.agr.gc.ca/atlas/supportdocument_documentdesupport/aafcLand_Use/en/ISO_19131_Land_Use_1990__2000_2010_Data_Product_Specifications.pdf

Federal, Provincial, and Territorial Governments of Canada. (2010). Canadian biodiversity: Ecosystem status and trends 2010. Ottawa: Canadian Councils of Resource Ministers. Retrieved from http://www.biodivcanada.ca/A519F000-8427-4F8C-9521-8A95AE287753/EN_CanadianBiodiversity_FULL.pdf

Hammermeister, A., Gauthier, D., & McGovern, K. (2001). Saskatchewan's native prairie: statistics of a vanishing ecosystem and dwindling resource. Saskatoon: Native Plant Society of Saskatchewan. Retrieved from https://www.npss.sk.ca/docs/2_pdf/NPSS_SKNativePrairie-TakingStock.pdf

Jenkins, C. & Joppa, L. (2009). Expansion of the global terrestrial protected area system. Biological Conservation 142 (10), 2166-2174. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2009.04.016

Johnston, M. (2017, January 27). Wetlands and carbon: Filling the knowledge gap. Saskatchewan Research Council. Retrieved from: https://www.src.sk.ca/blog/wetlands-and-carbon-filling-knowledge-gap

Mosher, D. (2012, March 22). Grasslands more diverse than rain forests: In small areas. National Geographic. https://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2012/03/120320-grasslands-rain-forests-species-diversity-environment/

Roch, L. & Jaeger, J. (2014). Monitoring an ecosystem at risk: What is the degree of grassland fragmentation in the Canadian Prairies? Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 186(4), 2505-34. doi:http://dx.doi.org.libproxy.uregina.ca:2048/10.1007/s10661-013-3557-9

Vaadeland, G. & Richardson, K. (2016, March 21). Grasslands, forests & wetlands - Nature's carbon capture & storage solution. Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society. Retrieved from http://cpaws.org/blog/grasslands-forests-wetlands-natures-carbon-capture-storage-solution

World Wildlife Fund. (2017). World Wildlife Fund 2017 Plowprint Report. World Wildlife Fund Northern Great Plains Program. Retrieved from https://c402277.ssl.cf1.rackcdn.com/publications/1103/files/origina/plowprint_AnnualReport_2017_revWEB_FINAL.pdf?1508791901

Wruck, G.W. & Gerein, K.M. (2003). Native plants, water and us! Native Plant Society of Saskatchewan Inc. Saskatoon: Native Plant Society of Saskatchewan Inc.